NEWS

Midday Live with Laura Rogers

On Tuesday November 14, Ron Schmidt, our Executive Producer, was Laura Rogers' guest on Midday Live on WBKO (ABC 13) in Bowling Green, KY. She interview Ron about our film. If you missed the interview, or don't live in the area, you can check the video below.

Appalachian wisdom for kids

Featured on October 17th in the Harlan Daily and the Middlesboro Daily News.

APPALACHIAN WISDOM FOR KIDS

By Ron Schmidt Contributing Writer

Courtney Hall recently wrote on her blog, The Bourbon Soaked Mom, “I hope my kids appreciate growing up Appalachian. I hope they fly down gravel roads with scraped knees and dirty bare-feet and revel in the raw and rowdy beauty of a summertime spent picking blackberries and killing copperheads with a garden hoe. I hope they relish that same sense of freedom.” She goes on in a more serious tone saying, “I want for them to understand that the most important things in life are not derived from material wealth. I am not a cultured person who has been around the world, so there may be a million ways for a person to come to this realization, but I know that truth came to me, and it was from growing up in these mountains.” Courtney’s “truth” I’ll call “Appalachian Wisdom.”

Nothing was hidden in the Appalachia I grew up in. Poor and rich were in the same schools – which were separated by race. While the mountains locked you into your surroundings, it gave you the sense you were a part of something. And for better or worse, you weren’t going anywhere. But as we moved on or stayed, I do think we learned things living in the mountains that made us the people we are today. I think all of us understand the wisdom received from the mountains.

Here’s an example. We moved from the city to the mountains in the early ‘60s for my dad’s job. The principal of the middle school told my parents that regardless of where you come from, you are placed in the so called middle or average class. Back in those days parents trusted educators, hey my dad never went further than 8th grade because of the Depression. So I started the 6th grade not knowing anyone, but also in a class with kids not as given to as the brainier kids in many ways.

Into the Melting Pot

It was the best thing that ever happened to me, because I got to know kids who were poorer than most, with parents not as fortunate as others. I felt comfortable with my classmates; we played on the same football team and most of all I got to know kids that I would have never met, should I have been put in the top class.

This experience gave me a comfort level in being with people from different walks of life which enhanced my business and personal life. We didn’t use the word empathy in those days but I developed an appreciation of what people go through, their challenges and how they handled conflicts. This small slice of life experience contributed to my Appalachian Wisdom.

I’ve written a script for a movie based on a true story from the mountains. The story is about three kids and a baseball team and how they handled adversity and conflict in a world that certainly wasn’t perfect in the early 1950s. It’s a beautiful story about hope for kids. I am curious about what stories you would tell about your childhood in the mountains, a story that would add to the wisdom for kids, a story that would give hope to kids in a world torn with violence and strife. For you baby boomers, what stories would you tell your kids and grandkids about growing up in Appalachia?

What’s Your Story?

My first question is: Do you have a story about a teacher or neighbor, about someone in your family or friend, a team, or a story about a tragedy? Would your story offer hope for kids? Does it have uniqueness to Appalachia? My second question is would you share your story? Be truthful (mountain people can smell a lie) but be optimistic and if you see how something can be done better today, please share it. Also, please try to keep your story to 500 words. What stories can you tell and suggestions you can make that not only give Courtney’s kids an appreciation for Appalachia, but also adds to their wisdom and hope?

Ron Schmidt is the creator and executive producer for the film This Field Looks Green To Me which will be filmed in Appalachia Kentucky in 2018. See his recent article in this publication September 2017; Answer the call to ‘feed’ our kids. He is a practicing CPA in Cleveland, Ohio. You may contact him at rschmidt@cbscpasllc.com For information on the movie please go to: www.thisfieldlooksgreentome.com

RELEVANCE OF THIS STORY

State authorities in New Hampshire are investigating a possible hate crime after a family reported that their 8 year-old son was pushed by teenagers off a picnic table with a rope around his neck, injuring him. At a cozy resort town in Slovakia where folks from the Middle East come for holiday, a 22 year-old walked up to a group of Muslims and began berating them at an outdoor café and later came back and smashed windows. The CEO of an extremely successful start-up in San Francisco resigned due to accusations of sexual harassments and lies. A 42 year-old mother of four from Akron scheduled to be deported was granted sanctuary in a Cleveland Heights church. And yet we hear epithets’ defaming political correctness like it’s a macho badge of honor permitting us to subscribe to name calling and hate.

The heroes of This Field Looks Green To Me, 12-year-olds Sadie Mae, Charlie, and Jaybird were born into a world were name calling and hate were not only present but it was protected under the law. Not only did this allow adults not to be aware that their actions could affect the lives of others in the Jim Crow society, but it was customary practice. This story is told through the eyes of the three kids and we see how they dealt with the conflict in their times.

Are we going back to Jim Crow days? Is the disrespect for one another the law of the land today? Or can we learn from these three? Can we put ourselves in their shoes 60 years ago and witness the lack of humanity they experienced? Can we understand what life was like with segregated schools, theaters, and eateries? Can we not learn from their experiences so as not to repeat travesties of the past? Can we be role models to kids today like Jaybird, Sadie Mae and Charlie?

“An Enormous Spider Web”

This Field Looks Green To Me gives perspective to our world today. We all have our own struggles and when we take the time to listen and become aware of someone else’s story, we begin the process of thinking about someone other than ourselves. In the movie’s story the symbolism of the ‘spider web’ is that the world is an enormous spider web and if you touch it, however slightly, the vibration ripples to the remotest perimeter and the drowsy spider feels the tingle.

As a society (the web) we are all interconnected and one’s irresponsible actions can have a damaging effect on others. Jack Burden, the main character of Robert Penn Warren’s All the Kings Men, witnessed the destructiveness of immorality and the bravery following redemption. If we thought the Jack Burden’s of the world existed only a century ago; look around, they are still with us.

Jodi Picoult has chosen to tackle our humanity as the driving force in her most recent novel. In her acknowledgement to Small Great Things, she says that talking about race is difficult, but that “we who are white need to have this discussion amongst ourselves. Because then, even more of us will overhear and – I hope – the conversation will spread.”

Keeping the Adults Out

Unfortunately for kids, we haven’t kept society away; we weren’t able to as Harry Hoe (a character in the movie) said “to keep the adults out.” As adults and society, we owe more to our kids. We have a responsibility to talk about race and our humanity and how we treat others.

This movie opens the door for multiple generations to do just that. Our hope is that This Field Looks Green To Me will provide an opportunity for parents and grandparents to have serious discussions with their children and grandchildren about such an important subject. It’s not too late, but we need to do this now. Right now.

Answer the call to ‘feed’ our kids

As featured in the Middlesboro Daily News and the Harlan Daily Enterprise

Do children go hungry in America today? Are their home lives chaotic? Do families struggle to get by? Are kids gunned down in the streets by gangs? And are opioids affecting our kids? The answer in too many cases is a definite “yes.”

In 10-year-old Kaylie’s home in eastern Illinois, the River Bend Foodbank has seen numbers rising 30 percent to 40 percent since the recession. She spends time collecting cans on the railroad tracks – earning between two and five cents per can. The hardest part of dealing with her family’s financial difficulties is ignoring hunger in her stomach. “I’m just starving…we don’t get three meals a day.” A published report states that 17 million kids living in U.S. households cannot count on reliably getting enough food.

Sixteen-year-old Daylan of Cleveland anguishes over the deaths of his boyhood friends killed in the streets. He grew up on East 105th Street between Superior and St. Clair avenues (an area also known as “10-5”). He saw a lot of his friends die before they even finished high school. A popular author talks about his “grim future” as a kid and what it feels like to “nearly give up on yourself” and how a “handful of loving people rescued me.”

The 24-year-old son of a northeastern Ohio police chief overdosed on opioids and died. While these are not stories from Appalachia, kids everywhere have similar struggles.

What can we do to help kids throughout this country? Every kid requires food and a stable home environment. To be successful every kid needs to be encouraged; they need confidence, a belief in themselves and the possibility to dream. They need someone to guide them.

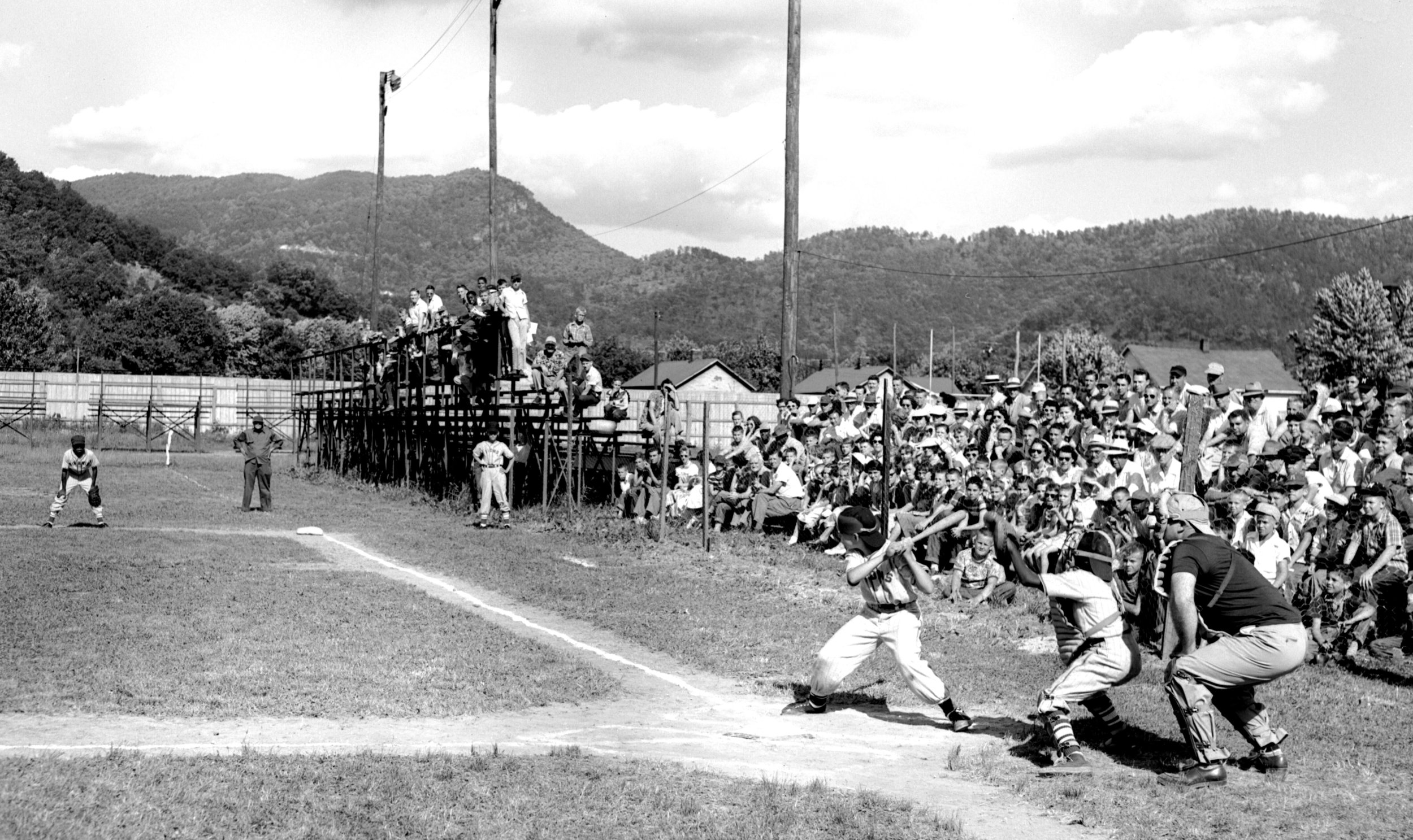

A true story that happened in Middlesboro in 1953 is a shining light – both locally and nationally – that shows what small groups of determined people can do to help kids. Eight men who founded the local Little League Baseball program “fed” these boys desire to compete and be better, to gain confidence, to dream, and to believe in themselves.

When Harry Hoe, Roy Stapleton and Cotton Rosenbalm returned from Europe after fighting the Nazis, they turned their attention to the kids of Middlesboro. They gave kids the opportunity to play organized baseball, both white and black kids. Our Middlesboro story can say a lot to kids in our country today about hope. Where is the leadership today who cares about kids? What can you do to answer Harry’s call to “feed” our kids?

Ron Schmidt is the creator and executive director of the film This Field Looks Green To Me soon to be shot on location in Middlesboro and Bowling Green. For movie info: www.thisfieldlooksgreentome.com.

GREEN FIELDS INITIATIVE

Houses built after World War II in the 1950s surrounded the vacant land in my Kentucky neighborhood. At the end of every other street, kids built their own ball fields – no parents were involved. Some kid borrowed his dad’s lawnmower and we scratched out foul lines and played ball. We learned from each other, playing ball morning to night during the summers. The most trouble I got into was when a great aunt would pass by the field on the way to a relative’s and I wouldn’t acknowledge her from a distance. Then I would hear about it from my mother.

Today playing baseball has risen to a new level. Kids only play where adults have organized their “playtime” and at 8 years-old, they’re “supposed” to “play” 55 games for the beloved travel team on a manicured field. That’s the kids in the suburbs. Unfortunately kids in the urban areas don’t have the fields to play on and where they may exist, violence is always around the corner.

The number of kids of color playing baseball in our country has dropped to an all-time low. Football and basketball are the dominant sports for those fortunate enough to stay away from gangs. I’m told gangs start recruiting as early as 8 years-old. And even if they aren’t with a gang, our urban areas are treacherous for kids to maneuver. And in more recent years the relation of cops and kids has deteriorated, remember Ferguson and Baltimore.

Major League Baseball and Little League Baseball are very much aware of this trend. Both have initiatives to attract African-Americans and Latinos in our country to play baseball. And they have built some ballparks in a first step toward accomplishing these goals. But there are not enough and they have left out an important player: the men and women who service our urban areas: police, fire, rescue, and other service responders.

Think about this: what if starting at 6 years-old, kids and service providers built ball fields together in the urban areas like we did when we were kids? Nothing fancy! With all the vacant lots in the cities where foreclosed and abandoned houses are torn down, we could build probably 60 fields in Cleveland alone. And with that, these kids who lack family role models can get to know local cops, they’ll have something to do in the summer, something other than joining gangs. And when that 6 year-old is 16 and walking down 105th street, officer Mack will recognize him and say: “Hi, how are things going in high school. And which colleges are you looking at?” Think about it. It worked decades ago, and it can work again today.

- Ron Schmidt

Green Fields Initiative

Many people don't know this, but Ron spends much of his spare time mentoring young Jr. High and High School kids in the Cleveland Ohio area. One of them, a young man name Daylan Jernigan, has been featured on DomoroSports.com this month.

It was Daylan who inspired Ron to create the "Green Fields Initiative" which is working to build little league fields in inner-city areas where they are needed. And to develop little leagues coached by Police, Fire, and Medics to build healthy relationships between first responders and the communities they serve in.

One of the many outcomes our film This Field Looks Green to me, is to serve as a platform for the Green Fields Initiative.

To ready Daylan's story click the link below.

http://dimorosports.com/2017/08/23/st-edward-eagles-football-daylan-jernigan-dimoro-sports-profile/

Talk of The Town: Interview

Ron was featured on the local MCTV program "Talk of The Town: with Dr. Ron Dubin"

Talk of theTown is a bi-weekly tv program hosted by our very own Dr. Ron Dubin. The show airs on Mondays and Wednesdays from 7:30-8pm on MCTV cable channel 22. Our unique guests include various business and community leaders, creative artists, educators and others involved in our local communities.

Friday July 14th, 2017

Ron's visit to the Bowling Green Kiwanis Club, featured on the front page of the Bowling Green Daily News.

Wednesday July 12th, 2017

Ron Schmidt will be the special guest speaker for the Bowling Green, KY Kiwans Club, on July 12th. There he will present his passion and vision for the film and his desire to shoot part of it in Bowling Green itself. The meeting will be held at 12:00pm

First Christian Church.

1106 State St

Bowling Green, KY, 42101

United States